The Preservation Philosophy for the Akin House Comes Together with the Phase III Project Work

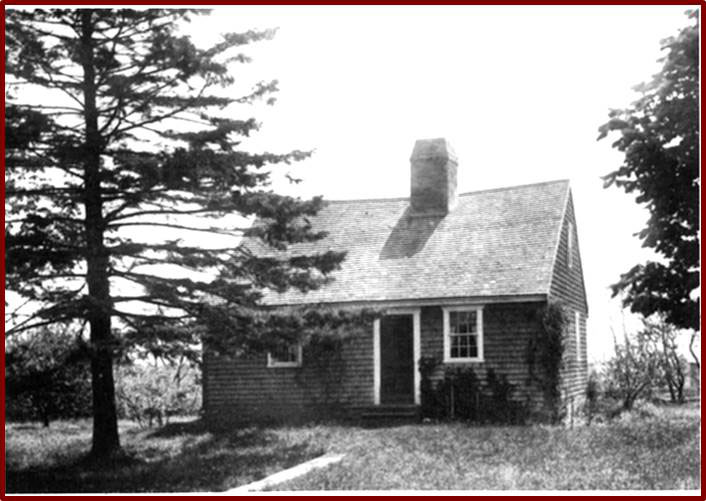

The above image of the formal parlor provides an example of the application of four historic treatments explained below. The original pine wall boards installed perhaps just a few years […]